In many organizations, the first reaction to an integrity issue is to ask management to “set the tone.” This principle is adopted by standards such as ISO 37001: if management clearly displays its values and commitment, teams will follow.

However, in practice, this message does not always translate into sustainable behaviors. Internal investigations, official communications, or exemplary sanctions can produce an immediate effect, but are not always sufficient to create a collective dynamic. For example, in a tax administration, an agent reported irregularities in the awarding of contracts. Management had adopted an official reporting channel, but the agent feared retaliation and isolation. Ultimately, it was the discreet support of colleagues, who relayed information and confirmed certain facts, that helped legitimize the alert and protect the whistleblower. Without this support network, the formal mechanism would have remained a dead letter.

The question then arises: can change originate solely from the top, or must it be nurtured by the strength of relationships among colleagues?

The Indispensable but Limited Role of Management

The history of leadership theories clearly demonstrates the importance of the model set by leaders. Burns spoke of transformational leadership, Treviño of social learning: in both cases, exemplarity matters. A leader perceived as fair, consistent, and credible can inspire their teams.

However, this inspirational role is not sufficient. In practice, management’s message only gains strength if it is relayed, appropriated, and discussed by teams. In other words, trust is built not only from the central figure, but through daily connections among colleagues.

When Networks Make a Difference

But what if the key to change did not lie solely with leaders, but in how individuals are connected within the organization?

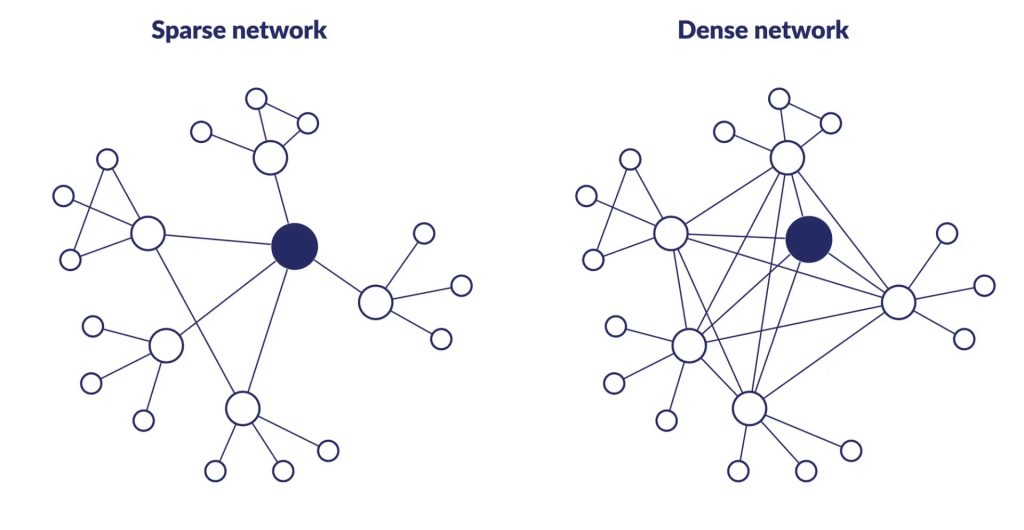

Network theory shows that the diffusion of behaviors depends less on a central figure than on the density of relationships among colleagues. In a sparse network, the message of integrity remains fragile, even if management conveys it with conviction. Conversely, in a dense network with numerous connections, ethical behaviors are more likely to spread and become deeply rooted.

For example, in the diagram below, change will circulate more easily in the dense network than in the “sparse” network where the leader is central but is actually poorly connected and thus has little influence.

For example, in a pharmaceutical company, management had established strict rules for declaring any conflicts of interest. However, several employees hesitated to report their external collaborations for fear of harming their careers. It was only when colleagues began discussing their dilemmas and the pressures they faced with each other that a greater number dared to declare their situations and value transparency. The change came from collective discussions, not solely from the written rule.

Damon Centola’s research confirms that convincing an active minority can be sufficient: approximately 25% of group members can trigger a chain reaction. Similarly, Granovetter’s threshold model illustrates that everyone has their own “tipping point” before adopting a new behavior, often influenced by what they observe in their peers.

Concretely, this means that an integrity project succeeds not only through the quality of codes or the exemplary nature of management, but also through the way individuals are connected to each other. Informal exchanges, mentorship, and daily discussions play a decisive role. Leadership must therefore create the conditions for a living network: spaces where ethical behaviors circulate, strengthen, and become the norm.

Building an Integrity Culture with Teams

A strong integrity culture therefore rests on two pillars:

- leaders capable of setting a course and embodying values;

- empowered, connected, and engaged teams that disseminate these values through their daily interactions.

The balance between these two dimensions is essential. Too much emphasis on compliance and the leader’s figure can create excessive dependence and hinder initiative. Too little framework and managerial support can leave room for rumors or complacency.

How Ethicor Supports your Teams

At Ethicor, we help organizations find this balance.

- Rapid Diagnosis: identify relational and organizational blockages that hinder trust.

- Team Support: facilitate workshops where employees jointly define integrity levers adapted to their reality.

- Leadership Support: assist leaders in supporting these collective dynamics and aligning compliance with the daily lives of teams.

- 90-Day Implementation: support the rapid application of co-constructed recommendations, with monitoring and adjustments.

The tone set by management paves the way, but it is the strength of the collective that drives progress. Ethicor helps you transform this potential into reality.

References

Brown M. E., Treviño Linda K., & Harrison D. A., 2005. Ethical leadership: A social learning perspective for construct development and testing, Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, Volume 97, Issue 2, pp. 117–134.

Burns J.M.G, 1978. Leadership, New York: Harper Torch Books.

Centola D., et al., 2018. Experimental evidence for tipping points in social convention, Science 360, pp. 1116-1119.

Granovetter M., 1978. Threshold Models of Collective Behavior, The American Journal of Sociology, Vol. 83, No. 6., pp. 1420–1443.

Nicaise, G. 2022. Strengthening the ethics framework within aid organisations. Bergen: U4 Anti-Corruption Resource Centre, Chr. Michelsen Institute (U4 Issue 2022:8).

Treviño, L. K., Brown, M., & Hartman, L. P. 2003. A Qualitative Investigation of Perceived Executive Ethical Leadership: Perceptions from Inside and Outside the Executive Suite. Human Relations, 56(1), 5-37.